PASSY MUIR'S VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 PDF FILE

PASSY MUIR'S VOLUME 4, ISSUE 1 PDF FILE

Peter S. Sandor, MBA, MHS, RRT, PA-C, DFAAPA, FCCM

James E. Lunn, MBA, MHS, RRT, PA-C, DFAAPA, FCCM

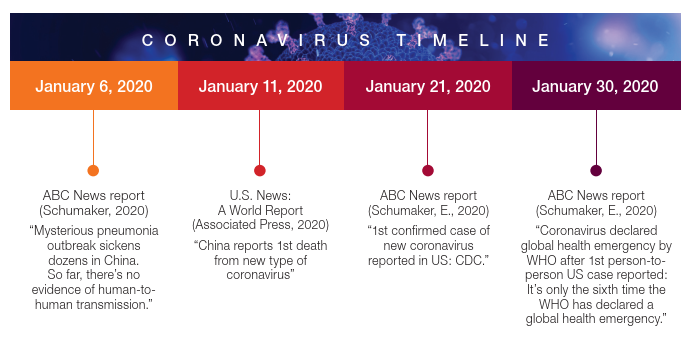

We all remember these headlines, but who would ever have thought that these events would trigger a pandemic that would threaten our lives, those of family and friends, and the lives of every person around the world? In addition to the lives lost, America’s robust economy crumbled over the course of days. In the early stages of the pandemic, unemployment rates in the US reached a record high of 14.7% (Falk et al., 2020) and the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped by a staggering record 31.4% in the second quarter (BEA, 2020). This drop may be compared to the Great Depression when the GDP dropped by 30%; however, the Great Depression lasted for several years and had a much more significant impact overall (Economic Impact, 2020).

First Cases of Coronavirus

In January of 2020, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) confirmed the first US coronavirus case in Washington State. The public received confirmation from the CDC of the first local transmission occurring in California during February of 2020. Soon after this announcement, cases started to emerge in New York. As residents of Connecticut, sitting on the couch and watching the local news that was providing pandemic-related headlines, even though skeptical, we began preparing. Was this the calm before the storm, or were we just overreacting? As New York City was running out of intensive care unit (ICU) beds, cases started to appear in Connecticut.

It was starting to sink in, as physician assistants working in the surgical intensive care unit of a level one trauma center, we were going to be one of those healthcare providers on the front lines.

Our First Patients

On March 12, 2020, the hospital admitted its first patient, and soon the hospitalist service and the medical intensive care unit were focusing their efforts on managing COVID-19 patients. Initially, things were manageable. With the state-mandated shut-down of non-essential workers, it was thought that we may avert the surge New York City was experiencing. Eventually, as the case count continued to rise, our hospital’s incident command center was activated, elective surgeries were halted, and the local community was afraid to step near a hospital. As a result, the hospital census initially declined, but was later inundated with more and more patients who were infected with COVID-19.

Since most areas of the hospital were shut down, many colleagues were furloughed. Simultaneously, COVID-19 admissions were rising, which resulted in an environment never before experienced - a disproportionate distribution of work. There was no COPD exacerbation, no appendicitis, no pneumonia - just COVID-19. These critically ill patients, who were initially located in the medical ICU (our designated COVID-19 ICU), were flooding the surgical ICU, cardiac ICU, the pre-operative area, and postoperative areas. This was when involvement in managing these critically ill patients became real. Without hesitation, our team of eleven physician assistants and nurse practitioners started overseeing one of the critical care units to off-load some of the medical team’s responsibilities. Walking into the COVID-only ICU was daunting. Many thoughts circulated – to trust personal protective equipment? To trust the ability to properly don and doff PPE? What was the risk of contaminating ourselves, other colleagues, or even other patients? Reports were that front-line workers across the country were becoming infected, and some were even dying. Would this be a fate healthcare workers possibly faced? What made this so terrifying was that the enemy was invisible; we were fighting a war against something we could not see, hear, taste, smell, or identify. Moreover, we did not have ammunition to fight this war. The unknowns far outweighed the knowns with COVID-19.

Sicker than the Sick We Knew

After working in a 600-bed tertiary care hospital for 20 years as physician assistants, what sick is and how to treat sick was known. Well, these patients were sicker than the sick we knew. As a result of

the visitor restrictions, family were prohibited from entering the hospital, and many patients would pass away without family at their side. This did not happen on one occasion; this was becoming the new normal. Each of these critically ill patients required a tremendous number of resources and manpower. Initially, treatment included hydroxychloroquine (immunosuppressive and anti-parasite drug, typically used for malaria), but as new data became available, recommendations continued to change, and soon, we stopped using hydroxychloroquine. We then used Lopinavir/Ritnovir (HIV antiviral medication), then Remdesivir (broad-spectrum antiviral medication), then steroids, and then convalescent plasma (antibody-rich product from blood of people who had the disease caused by the virus). The treatments were everchanging; however, improvements were minimal. As you can imagine, patients were scared and lonely; at times, some of the most impactful care was spent at the patients’ bedside, holding their hand so they were not alone.

From a respiratory standpoint, the thought was to intubate early and avoid non-invasive ventilation and high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) because of potential aerosol generation. However, with time, we realized that most patients who were intubated were never extubated, and as more data became available, there was a shift in practice to avoid intubation. Instead, treatment began to focus on noninvasive ventilation and HFNC. It was a type of respiratory failure that was uniquely different when compared to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) previously seen. In addition, to avoid mechanical ventilation, these patients showed significant benefit from proning.

Proning has been the process of turning a patient with precise, safe motions from their back to their stomach which relieved the pressure of gravity and assisted with improving oxygenation (Penn Medicine Physician Blog, 2021). In the past, this was something rarely performed as it required the use of a specialty bed to secure the patient and prevent tube dislodgement. Without access to these beds, the alternative was something learned from our European colleagues, called the “Burrito” technique (Wiggermann et al., 2020). Working with physical therapy and occupational therapy colleagues, a proning team trained in this technique was created and responsible for successfully flipping many of the sickest patients. We also were worried about running out of ventilators. During this time, the media was fixated on this issue; however, everything was running low - including dialysis machines, dialysate solution for dialysis, IV pumps, and numerous medications.

As the COVID-19 census increased, overflow make-shift ICUs in the pre-operative and post-operative units were deployed. COVID-19 forced us to tear down our silos and interact with members of different service lines more than we ever had before. We were now working collaboratively with nurses, doctors, advance practice providers, respiratory therapists, and rehabilitation staff; many with whom we had never worked. This shift in practice patterns involved a steep learning curve and a need to develop mutual trust rapidly, especially with the constant changes. We relied on each other, respected each other, and trusted each other. Professional title did not matter nor did seniority. It was incredible and inspiring to see how successful collaborations were under these conditions, even though from different teams; one thing that remained constant was how no one ever said, “I cannot do this.”

Finding Serenity in a Pandemic?

Heading to work each day was a little different without traffic. The drive to work offered time for reflection, listening to music, or putting the window down for some fresh spring air. This time provided the serenity needed before arriving at work.

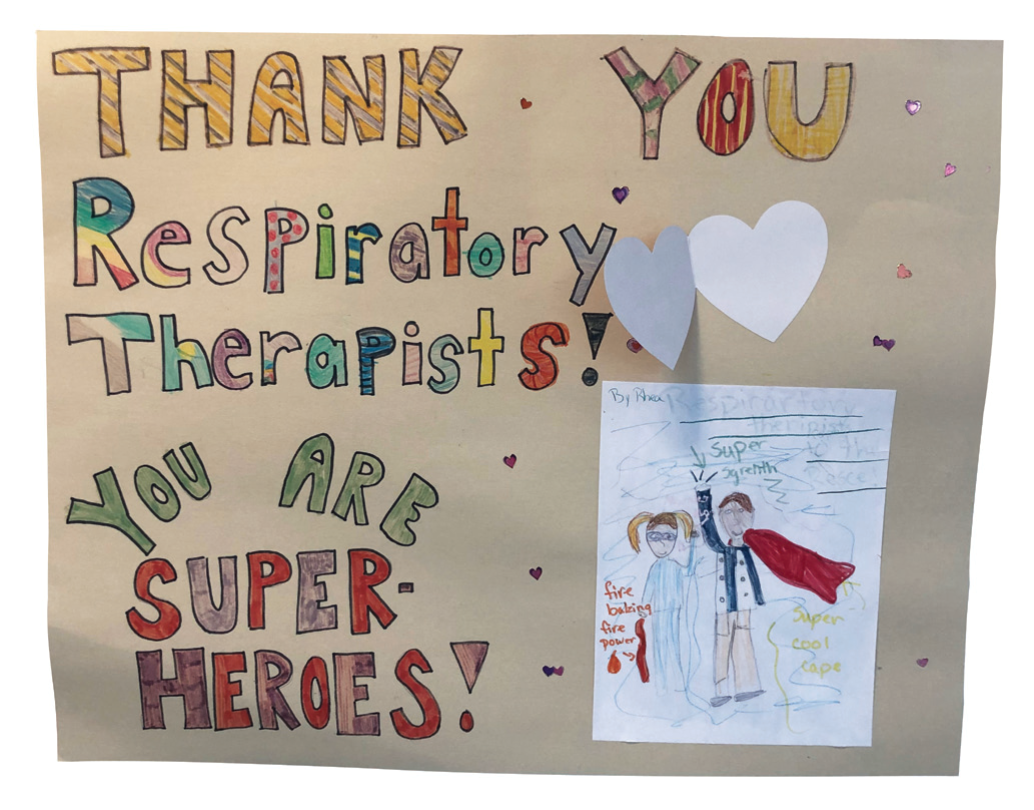

Daily, the bridge connecting the parking garage to the hospital displayed pictures and posters handmade by the local school children. One I remember vividly is not all heroes wear capes written in crayon by a seven-year-old. These posters were so precious that they would bring a lasting smile - a smile that lasted through the temperature check and applying my surgical mask. And continued as I walked to the locker room, changed into my scrubs, grabbed my eye protection and N-95 mask, and then headed to COVID Cave, called a cave as there were no windows to know whether it was day or night.

Peter S. Sandor

Medicine is humbling. As was to be expected, working in an ICU exposed us to death. However, knowing most patients will survive and will go back to a good quality of life made the job all worthwhile. In essence, the wins and the lives saved kept us, and continues to keep us, working in critical care.

With COVID-19, things were a little different. A recent publication reported that 40% of COVID-19 patients in the ICU would die and 59% of those who received mechanical ventilation would die (Tzotzos et al., 2020). These statistics were profoundly different from what had been known prior to COVID-19. Working in this environment was not only physically and mentally exhausting, but psychologically and emotionally exhausting as well. Truthfully, it was a privilege to care for these patients. While reflecting on these experiences, it would be hard to imagine it happening any other way. Much was learned and new protocols were designed. Though our Surgical ICU team worked hard, the real heroes were and are the nurses and respiratory therapists who continuously sacrificed while working intimately with this COVID-19 population.

Light at the End of the Tunnel

By Summer 2020, four months into this mess, a light was seen at the end of the tunnel. COVID-19 cases declined significantly with only a handful of cases in our hospital. It was the first time we were able to spend time together outside of work. It was on Saturday, July 11th, 2020 that we invited family over; our children had a chance to play by the pool, and the adults toasted with champagne to celebrate our belated MBA graduation. Life was good!

Hospitals on the other hand had to deal with the aftermath of the destruction which was unrelated to patient care. It has been estimated that U.S. hospitals have lost over $200 billion (American Hospital Association, 2020), forcing many hospitals to either close their doors or file for bankruptcy (Ellision, 2020). Many hospitals turned to significant layoffs and restructuring to remain viable. Our hospital survived, and we were grateful to still have a job.

Second Wave

Then came the second wave. October of 2020, COVID-19 cases began to rise, and this time the pandemic was widespread and with little opportunity to shift resources. Was this second wave going to be worse? Would the previous layoffs impact capacity? Would healthcare professionals have the mental, physical, and emotional stamina to endure another wave?

Healthcare workers were reaching emotional exhaustion,

the hallmark of burnout.

At the time, when compared to California, you could say we were lucky as it related to capacity. In Los Angeles County, Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT) were told not to transport patients to the hospital who had little chance of survival. Additionally, they were told to ration oxygen as supplies were running low, and if you were lucky enough to obtain a ride to the hospital in an ambulance, you would most likely wait outside for several hours before getting through the door (Meeks et al., 2021). From a psychological and emotional standpoint, life was no longer as good. Throughout a career in medicine, good days, bad days, the ups and downs have occurred. Previously, with a few days of rest, resilience to bounce back happened, and this was true for most healthcare workers. However, this pandemic was not allowing days off; there was no time to bounce back. Healthcare workers were reaching emotional exhaustion, the hallmark of burnout.

Current State of the Pandemic

As we write this last paragraph, the COVID-19 numbers have begun to decline, vaccine rollout has become widespread, unemployment has been decreasing, and the global economy has begun recovering. This pandemic seems to be coming to an end, but it has permanently affected nearly every aspect of daily life. According to a survey performed by the Centers for Disease Control, 40.9% of respondents reported at least one new mental health condition related to this pandemic, 13.3% started a new substance to help relieve emotional stress, and over 10% have considered suicide in the last 30 days (Czeisler et al., 2020). These numbers are most likely conservative figures. COVID-19 has impacted the United States and other countries on many levels. Many movie theaters and banquet facilities have gone out of business. Restaurants, gyms, and stores were lucky if their businesses survived. Questions remain. Will we ever feel comfortable traveling or going to a concert again? Will we be able to safely hug, kiss, or shake hands with family and friends? Will we ever get back to our previous normal or are we just chasing pipe dreams and facing a new normal? These are some of the questions caused by COVID-19 but still to be answered.

References

American Hospital Association. (May 2020). Hospitals and health systems face unprecedented financial pressures due to COVID-19. Retrieved from https:// www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2020/05/aha-covid19-financial-impact-0520-FINAL.pdf

Associated Press. (2020). China reports 1st death from new type of coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/ articles/2020-01-10/china-reports-1st-death-from-new-type-of-coronavirus

Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2020). Gross domestic product, third quarter 2020 (Second Estimate); corporate profits, third quarter 2020 (Preliminary Estimate). Retrieved from https://www.bea.gov/news/2020/gross-domestic-product-3rd-quarter-2020-second-estimate-corporate-profits-3rd-quarter

Czeisler, M. E., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69, 1049–1057. http://dx.doi. org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

Economic Impact. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/ Great-Depression/Popular-culture

Ellision, A. (2020). 42 hospitals closed, filed for bankruptcy this year. Becker’s Hospital Review. Retrieved from https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/ finance /42-hospitals-closed-filed-for-bankruptcy-this-year.html?_ ga=2.219853148.417375660.1598795307-1480266349.1598449954

Falk, G., Carter, J. A., Nicchitta, I. A., Nyhof, E. C., & Romero, P. D. (2020). Unemployment rates during COVID-19 pandemic: In brief. CRS Report. R46554. Retrieved from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46554.pdf

Meeks, A., Maxouris, C., & Yan, H. (2021). ‘Human disaster’ unfolding in LA will get worse, experts say. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/05/ us/los-angeles-county-california-human-disaster-covid/index.html

Penn Medicine Physician Blog: Proning during COVID-19. (May 2021). Retrieved from https://www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/penn-physicianblog/2020/may/proning-during-covid19

Schumaker, E. (2020). 1st confirmed case of new coronavirus reported in US: CDC. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/1st-confirmed-case-coronavirus-reported-washington-state-cdc/story?id=68430795

Schumaker, E. (2020). Mysterious pneumonia outbreak sickens dozens in China: So far, there’s no evidence of human-to-human transmission. Retrieved from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/mystery-pneumonia-outbreak-sickensdozens-china/story?id=68094861

Tzotzos, S. J., Fischer, B., Fischer, H., & Zeitlinger, M. (2020) Incidence of ARDS and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a global literature survey. Critical Care, 24, 516. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03240-7

Wiggermann, N., Zhou, J., & Kumpar, D. (2020). Proning patients with COVID-19: A review of equipment and methods. Human Factors, 62 (7), 1069 – 1076. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720820950532

With a passion for quality and patient safety, we recently created Clear View Simulation, and just launched the new innovative and interactive tracheostomy trainer

(website: www.clearviewsim.com)